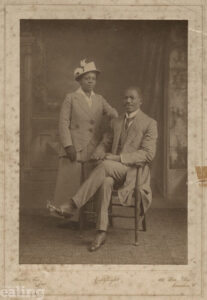

October is Black History Month. In the second of 2 local history articles, with the help of borough archivist Dr Jonathan Oates, we take a look at a prominent black man who, from Acton and beyond, battled racism and strived to overcome ignorance 100 years ago.

John Alexander Barbour-James was a former colonial civil servant in British Guiana, and a resident of Acton in the 1920s. In 2022, a plaque was put on his former home at 84 Goldsmith Avenue.

He was very prominent both locally and nationally in causes which affected black people, and his work took him across the country. The multi-talented Barbour-James was also an author and composer as well as a public speaker and organiser.

Work he carried out included for the African Progress Union, the League of Coloured Peoples (a British civil rights organisation), the African Patriotic Intelligence Bureau (which he founded) and the Association of Coloured People (of which he was president).

One of John’s messages he often gave to audiences was that people should look beyond old, stereotypical media images of black Africans as being savages and that racial differences were skin-deep. It often took some doing because audiences thought that he was exceptional or unusual, and he would have to say that he was not.

This message chimes with 2024 Black History Month‘s theme of Reclaiming Narratives.

Barbour-James would make use of the press to spread his message and The Acton Gazette proved particularly helpful and often featured his work on its pages, including the front page. He once wrote a letter to the editor that said: ‘On behalf of the African Progress Union and all Africans, I write to express

sincere thanks to you for your invariable intercept and courtesy in all matters by which they are affected. The persistent and continued services rendered on our behalf by your widely circulated journal in enlightening public opinion in this country about the correct viewpoints of the African peoples during a long period are very highly valued, and I fear it would be difficult for us to sufficiently render you what is your due.’

Unethical treatment

In 1924, the British Empire Exhibition was held in Wembley (it was also held the following year). Many people from overseas, especially from parts of Africa and Asia were involved in this as participants and visitors.

Local amenities in north and west London were placed on standby to help visitors if needed – including local health services.

However, the committee of Acton Isolation Hospital decided – and stated – that it would not treat any person of colour. The members said that this was because of the difficulties imposed by different dietary requirements and different medical needs.

Of course, this news did not go down well with many people and, at a meeting of Acton Council, Councillor Carter ‘expressed much indignation’ about this ruling. He said that, because the exhibition was to bring people together, such an attitude was neither logical nor humane. Councillor Mrs Forrester seconded this.

But some councillors supported the original decision. They argued that there were diseases that white people had not yet been affected by and that treatment ‘of our black brethren’ could be better given elsewhere. This was not a matter of ‘race prejudice’, they claimed, but of administrative necessity. Carter responded with: “You object to treat people of coloured races. Why not admit it?”

This argument was covered by the local newspaper. In the next edition, a journalist commented on the negative attitude shown by certain councillors. He wrote that not all black, brown and yellow skinned people were subject to tropical diseases such as sleeping sickness and worm foot. Not all ate exotic food. Many ate just as Europeans, used the same medicines and were in fact little different.

The journalist also consulted an expert with first-hand knowledge, who agreed: “Their treatment is, in the majority of cases, no more ‘special’ than that of white patients.”

It would be interesting to know if Barbour-James was the expert in question. Certainly, he was involved in the exhibition at Wembley.

Running in the family

John’s daughter, Amy, was born in Acton on 25 January – one of 8 children John had with his wife Caroline.

Inspired by her father, Amy became active in the civil rights movement herself and was involved in the African Progress Union and the League of Coloured Peoples, becoming secretary of the latter organisation in 1942. She died in Harrow in 1988, aged 82.

Photo at the top of this page is a detail taken from a photo of Caroline and John Barbour-James by Maull & Fox, circa 1910 © National Portrait Gallery, London, and reproduced under terms of creative commons.

READ MORE

Read the previous article this month, on the Bogle L’Ouverture bookshop.