October is Black History Month. As part of this, Around Ealing spoke to Dame Elizabeth Anionwu about her life and extraordinary achievements.

Dame Elizabeth, an Ealing resident for more than 50 years, is the country’s first sickle-cell and thalassaemia specialist nurse and a passionate advocate for improving healthcare for London’s Black community.

The question is not what has Dame Elizabeth achieved; it’s more – what else could she possibly have done in her career?

A nurse, lecturer, and Emeritus Professor of Nursing at the University of West London, she is a member of the Order of Merit, a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire, and a Fellow of the Royal College of Nursing (RCN).

Part of the Bobby Moore Academy in Hackney and an RCN award are named in her honour. Last year she was awarded her sixth honorary doctorate award, this time from the University of Greenwich. In 2025 she will travel to Dublin to receive her 7th award from the RCSI University of Medicine and Health Sciences. She even played a key role in the King’s coronation last May.

Dame Elizabeth at the King’s coronation

At the heart of her career was a dedication to improving healthcare options for the Black community in London. Her personal journey towards understanding her own Black heritage led her to playing a role in the development of Black consciousness in Britain in the 1970s.

An early encounter with nursing

As a child, Dame Elizabeth suffered with eczema so severe that she needed it tending to daily. Raised in a convent by nuns at Nazareth House in Birmingham until she was 9, it was during these difficult years that her future calling began to take shape. One nun stood out – a kind, humorous, and gentle woman who she later discovered to be a nurse.

“She was the only one who could change the dressings on my arms and legs without causing me pain because she used distraction therapy,” she recalled. “She would crack what I thought were really dirty jokes for children. She used the word ‘bottom’ – this holy woman used that naughty word! She would make me laugh, and while I was laughing, the dressing would be changed without me feeling a thing.” This nurse left a lasting impression, sparking Dame Elizabeth’s own desire to become a nurse.

She would go on to become the country’s first sickle-cell and thalassaemia specialist nurse in 1979, and help to establish the Brent Sickle Cell and Thalassaemia Centre. In 1998, the now Professor Anionwu created the Mary Seacole Centre for Nursing Practice at the University of West London.

Facing prejudice

Before her long and successful career, Dame Elizabeth first had to overcome the challenges of a childhood impacted by racism and physical abuse. “My maternal great grandparents were immigrants from County Wexford inIreland. And my father was Nigerian. One can only imagine what the reaction was when my parents got together.”

She recalls the post-Second World War period, an era rife with prejudice against children born outside of marriage and interracial relationships. “People didn’t understand all of that then. And so, I spent the first 9 years of my life in a children’s home.”

Life in care

Mary Furlong, Dame Elizabeth’s mother, was an exceptional student at Cambridge University when she met her daughter’s father, a Nigerian law student called, Lawrence Anionwu, and became pregnant. Mary’s parents originally planned to raise the baby as their own, to allow Furlong to continue her studies. However, when Dame Elizabeth was born and her skin tone revealed the reality of the situation, the plan was abandoned, and the child was placed into care.

Such an arrangement was not unusual at the time. But the big advantage for Dame Elizabeth is that her mum remained in constant contact.

“My mother never gave me up for adoption and I was in constant contact with her”, she said. “I grew up in the children’s home knowing that she wanted to make a home for me, and she was a regular visitor. So I never ever had any sense of rejection from her or her family.”

There were brutal aspects to the care she received at the home. But there was also plenty of love.

“There were traumatic episodes. I was a bed wetter. Treatment was harsh and it didn’t help. So that’s the negative. But I did Irish dancing. I was taught to play the piano by a nun. I think that I had people always looking out for me. There were more kind people than there were miserable, nasty people, fortunately.”

As the only child of colour there, she recalls longing to look like her friends. “I would wash my face 10 times in a row as a child to try and become white. I didn’t want to be different. I wanted to be like my friends.”

At the age of 9, Dame Elizabeth went to live with her mother and stepfather, who became physically abusive. As a result, she was sent to live with her maternal grandparents in Wallasey, Merseyside. She subsequently moved to London for nursing training.

Connecting with her dad

Everything shifted for Dame Elizabeth in March 1972 when she met her father for the first time. “That sorted me out. Totally. I describe it as completing the jigsaw of my identity, and I felt whole and I felt comfortable, confident, and happy.”

Their reunion was made possible by the late John Roberts QC, the first Queen’s Counsel of African descent, who she knew through the Caribbean Overseas Association in Acton, west London.

“He happened to tell me one day that he occasionally taught Nigerian law students,” she said. “So when I did get my father’s name and I didn’t know any Nigerians and I thought, well, John might be able to help me find out what part of Nigeria does my father’s name come from.”

After John offered to investigate, just days later, he called her with unexpected news – he had spoken to her father. He was not in Nigeria as she assumed, but amazingly was temporarily staying in north London, just 30 minutes away.

Dame Elizabeth only knew her father for 8 years before he passed away in 1980, but their time together made a lasting impact. “We found that we had the same taste in music and the same sense of humour.”

Black British consciousness in the 1970s

Another formative connection and influence for her came through her involvement with Jessica and Eric Huntley, a pair of pioneering Black political activists and publishers from British Guiana and based in Ealing. Dame Elizabeth began volunteering to sell the Huntley’s books, which focused on Black history and political education, at various events. This experience opened her eyes. Jessica Huntley, in particular, left a lasting impression on her.

Another formative connection and influence for her came through her involvement with Jessica and Eric Huntley, a pair of pioneering Black political activists and publishers from British Guiana and based in Ealing. Dame Elizabeth began volunteering to sell the Huntley’s books, which focused on Black history and political education, at various events. This experience opened her eyes. Jessica Huntley, in particular, left a lasting impression on her.

She said: “Jessica was wonderful, very influential for me. She had so much energy, and she was so driven. Jessica never asked you to do something – she told you to do it! We got on well, and she helped me enormously.”

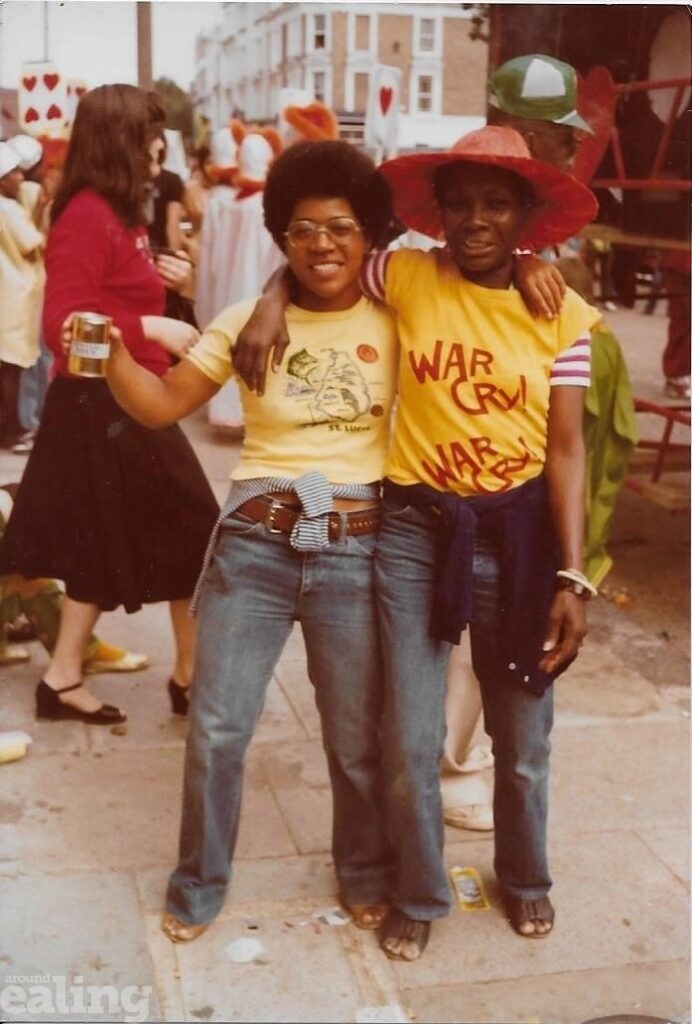

Dame Elizabeth and Jessica Huntley

You can read more about Dame Elizabeth in her memoir, Dreams From My Mother. It is an inspiring story about childhood, race, identity, family, friendship, hope and what makes us who we are.

Win a copy

We have a copy of the book to give away. Enter online now.