The lives of ordinary black women who lived and worked in London before the Second World War are not well known. Like many working class women, their lives are not easy to find in the archives, writes Caroline Bressey.

Their voices and opinions were not often recorded by reporters, unless exceptional circumstances drew particular attention to them.

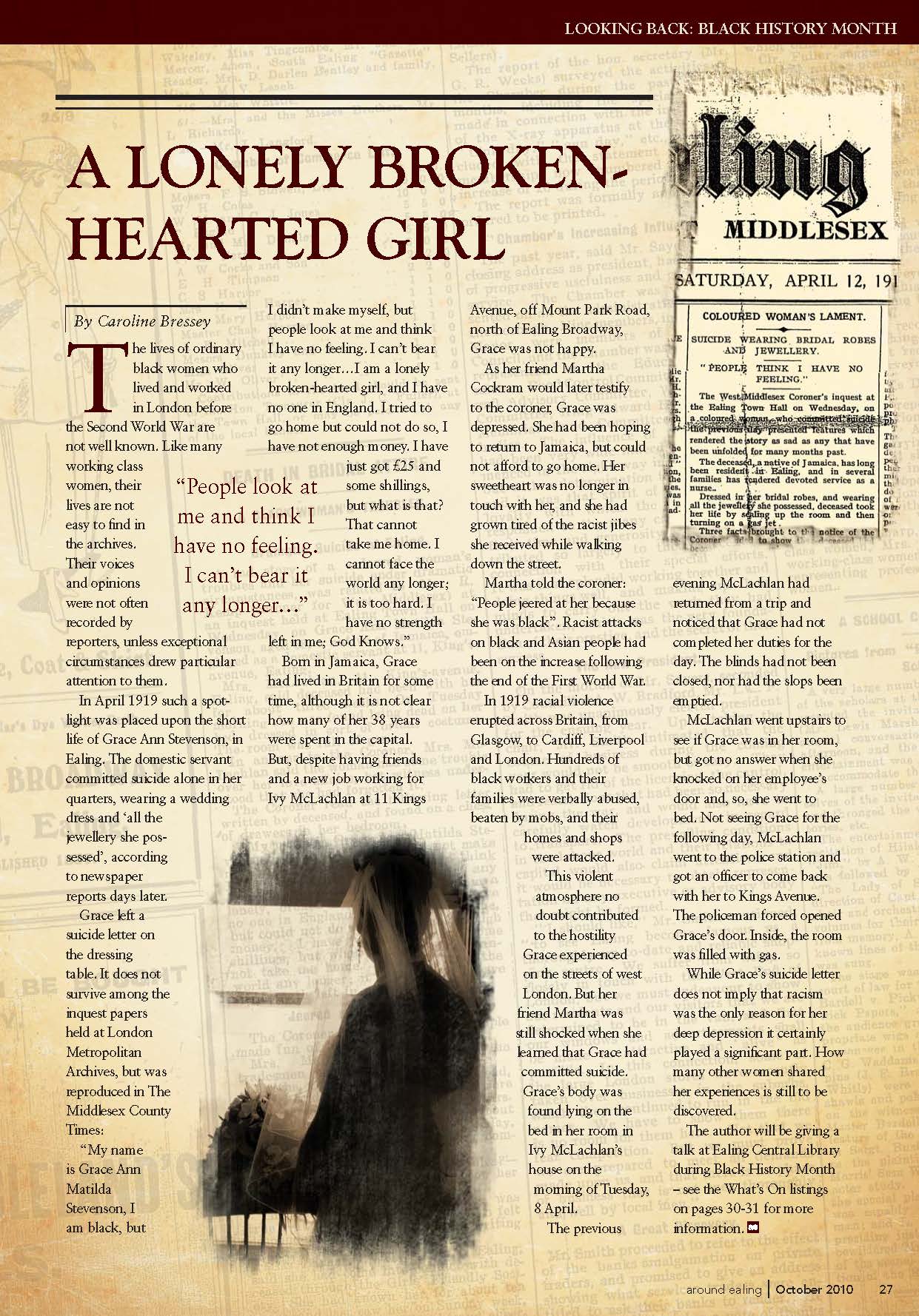

In April 1919 such a spotlight was placed upon the short life of Grace Ann Stevenson, in Ealing. The domestic servant committed suicide alone in her quarters, wearing a wedding dress and ‘all the jewellery she possessed’, according to newspaper reports days later.

Grace left a suicide letter on the dressing table. It does not survive among the inquest papers held at London Metropolitan Archives, but was reproduced in The Middlesex County Times: “My name is Grace Ann Matilda Stevenson, I am black, but I didn’t make myself, but people look at me and think I have no feeling. I can’t bear it any longer…I am a lonely broken-hearted girl, and I have no one in England. I tried to go home but could not do so, I have not enough money. I have just got £25 and some shillings, but what is that? That cannot take me home. I cannot face the world any longer; it is too hard. I have no strength left in me; God Knows.”

Born in Jamaica, Grace had lived in Britain for some time, although it is not clear how many of her 38 years were spent in the capital. But, despite having friends and a new job working for Ivy McLachlan at 11 Kings Avenue, off Mount Park Road, north of Ealing Broadway,

Grace was not happy. As her friend Martha Cockram would later testify to the coroner, Grace was depressed. She had been hoping to return to Jamaica, but could not afford to go home. Her sweetheart was no longer in touch with her, and she had grown tired of the racist jibes she received while walking down the street.

Martha told the coroner: “People jeered at her because she was black”. Racist attacks on black and Asian people had been on the increase following the end of the First World War. In 1919 racial violence erupted across Britain, from Glasgow, to Cardiff, Liverpool and London. Hundreds of black workers and their families were verbally abused, by mobs, and their homes and shops were attacked.

This violent atmosphere no doubt contributed to the hostility Grace experienced on the streets of west London. But her friend Martha was still shocked when she learned that Grace had committed suicide.

Grace’s body was found lying on the bed in her room in Ivy McLachlan’s house on the morning of Tuesday, 8 April.

The previous evening McLachlan had returned from a trip and noticed that Grace had not completed her duties for the day. The blinds had not been closed, nor had the slops been emptied.

McLachlan went upstairs to see if Grace was in her room, but got no answer when she knocked on her employee’s door and, so, she went to bed. Not seeing Grace for the following day, McLachlan went to the police station and got an officer to come back with her to Kings Avenue.

The policeman forced opened Grace’s door. Inside, the room was filled with gas. While Grace’s suicide letterdoes not imply that racism was the only reason for her deep depression it certainly played a significant part. How many other women shared her experiences is still to be discovered.

The author gave a talk at Ealing Central Library during Black History Month.

This originally appeared in Around Ealing October 2010