Montpelier Road is a quiet, residential street. Just over six decades ago, though, it was the scene of arguably one of Ealing’s worst crimes.

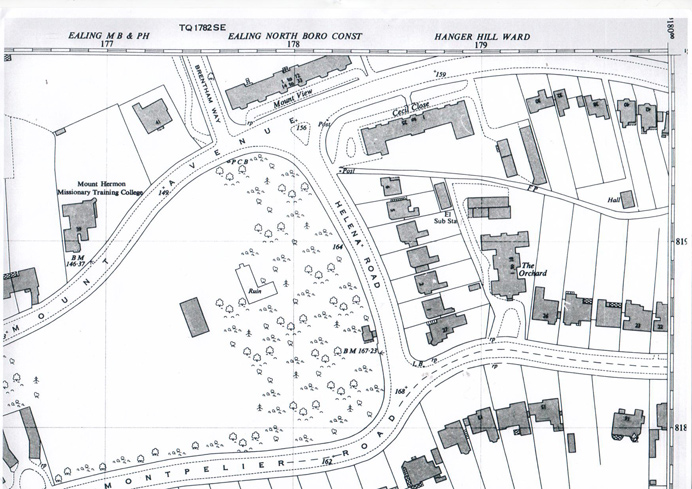

The road now has a mixture of late Victorian detached houses, as well as more recently built flats and smaller houses. The crime occurred at number 22, where the smaller houses of Magnolia Place now stand. At the time, the house was a home for elderly people.

On the morning of 11 February 1954, the housemaid, Eileen Thorpe, could not find her employers, Mary Menzies and her daughter, Mrs Chesney. They were not in their rooms nor did they appear to have left the house. Concerned about being alarmist, she contacted her employers’ relations who lived nearby. They arrived at the house and searched it, without initially finding anything untoward.

One room not searched, because it was locked and presumably in use, was one of the bathrooms. Eileen saw the key on the kitchen table and decided to check.

What she saw horrified her. The body of Mrs Chesney was in the bath, quite dead. The police were called and Superintendent Daws arrived. He quickly found, concealed in a spare room, the body of Mary Menzies, who had been hit around the head. It was later found that her daughter had been drowned in the bath.

There was no sign of a forced entry and no one had seen or heard anything suspicious. The family dogs had not barked in the night. However, Daws found that it was possible to enter the house by the footpath behind it and open the back window without any sound being made. People walking dogs had seen a suspicious man hanging about nearby last night and a man was seen walking quickly away after refusing a lift in the early hours. Presumably this was the killer.

Another twist to the tale was that, a few days later, Mrs Chesney’s estranged husband, Ronald, was found dead in a wood near Cologne. He had shot himself. He was a reasonably well known, yet still mysterious, figure in Ealing. He served as a Royal Navy officer in the Second World War but had been recently convicted for smuggling.

He had also made a settlement on marriage to provide his wife with an income for the rest of her life, to revert to him on her death. In 1927 he had been on trial for shooting his mother in Edinburgh, but was the case was ‘not proven’. His suicide note stressed that he had not killed his wife.

However, at the inquest at Ealing Town Hall, the verdict was that Mr Chesney was responsible for the double murder in order to get his hands on the money he had settled on his wife and because she had refused to divorce him. Forensic evidence gave credence to this and witnesses had seen him enter and leave the country on another man’s passport.

Two books were written in the 1950s about Chesney’s criminal career. In November a new book, drawing on hitherto unexplored archives, presented a fresh look at the life and crimes of Ronald Chesney and those whose lives he affected.

This story was the subject of a talk given by Dr Jonathan Oates at Ealing Central Library.