With the wedding of Prince William and Kate Middleton drawing close, it seems timely to take a look at the entries of a local diarist – because the events he recorded almost 80 years ago provide distinct parallels to the current day.

Alexander Kay Goodlet was neither Samuel Pepys nor Anne Frank, but his diary gives an insight into lower middle class life in Ealing in the 1930s, which was troubled by economic difficulties.

Goodlet lived at home with his parents and siblings in Granville Road, Ealing, during the course of keeping his diary, which covers the period 1934-1940.

Money was a constant worry, and there are many references to waiting for cheques. Demands from utility companies and tradesmen are frequently mentioned with dread. The pawnbroker was an occasional source of finance, too.

In a further echo of modern times, a royal wedding provided a distraction to the financial gloom – although this particular marital match-up received a less than enthusiastic response. He also discusses an address given by King George VI – which became the subject of the recent hit film The King’s Speech.

These events all came about after the death of the ailing and much-loved King George V. On 18 January 1936 Goodlet wrote, ‘The King is dangerously ill…I very much fear for him. Poor old gentleman, he has had a pretty hard life and somehow or other everyone seems to look on him as a relative’. When he went to a post box he found ‘an old gentleman at the pillar box was in tears’.

The Goodlet family then gathered around the wireless radio to listen to the announcement of the king’s death, ‘This waiting is horrible. Nobody in the room has spoken a word. The wireless of late years has brought the King very intimately into the lives of us all. Somehow it makes us all members of the family assembled to witness his passing’.

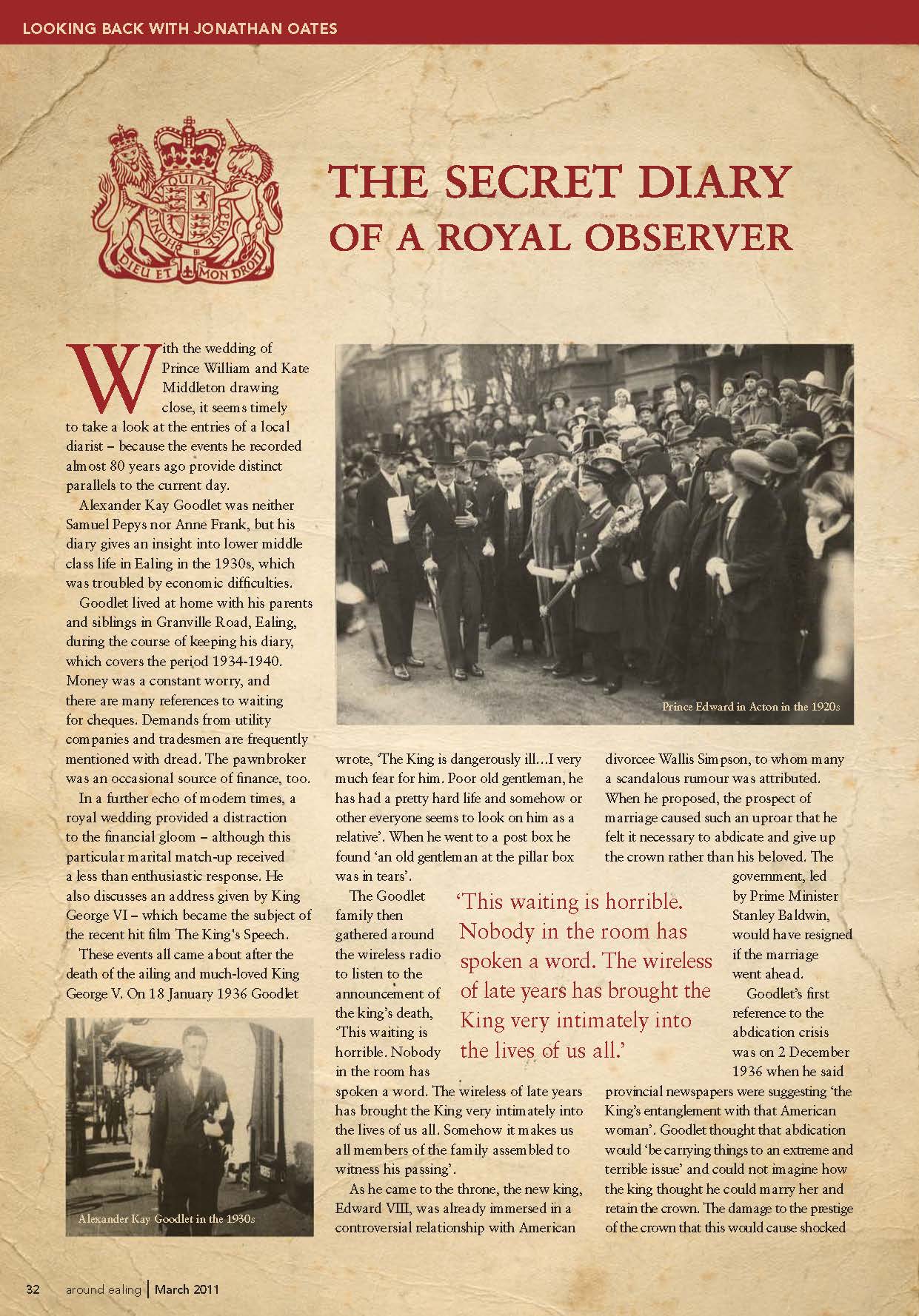

As he came to the throne, the new king, Edward VIII, was already immersed in a controversial relationship with American divorcee Wallis Simpson, to whom many a scandalous rumour was attributed.

When he proposed, the prospect of marriage caused such an uproar that he felt it necessary to abdicate and give up the crown rather than his beloved. The government, led by Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, would have resigned if the marriage went ahead.

Goodlet’s first reference to the abdication crisis in his diary was on 2 December 1936 when he said provincial newspapers were suggesting ‘the King’s entanglement with that American woman’. Goodlet thought that abdication would ‘be carrying things to an extreme and terrible issue’ and could not imagine how the king thought he could marry her and retain the crown. The damage to the prestige of the crown that this would cause shocked him and the matter quickly became the sole topic of conversation.

Writing in his diary, Goodlet thought that the marriage would go ahead, but was unhappy about it. But neither did he willingly support abdication.

He was involved in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR), and when the news broke in the national press that Edward’s abdication had occurred after less than a year on the throne, Goodlet wrote that ‘the majority of old naval blokes in the lower wireless room were vehement in their condemnation of the King’s decision’.

It seems Goodlet shared their views on ‘an act of public suicide unexampled in English history’. ‘I shall never understand it’. He thought Edward’s act would make younger brother George VI’s subsequent coronation more difficult. However, he wrote ‘I think he [George VI] will, however, make a splendid king’. He also thought that Edward would be remembered ‘in the hearts of the people as a glamorous, well-loved memory’ and that he found himself ‘profoundly moved’ by his abdication address.

Another major royal occasion was the coronation of 1937.

The family huddled around the wireless to hear the service and the procession, and numerous speeches – including by the newly crowned King George VI, who had a stammer. Goodlet wrote, ‘I confess I was a little ill at ease, for he sometimes makes long pauses in his speaking and one feels he will break down; but he never does, and resumes his speech quite naturally’.

In the evening the diarist and his brothers went out on to Ealing Common to see a bonfire and fireworks to celebrate the event. On the way back, he dropped in on a friend’s house and spent another two hours at a coronation party.

This originally appeared in Around Ealing March 2011